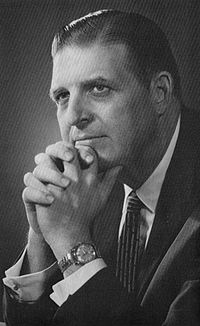

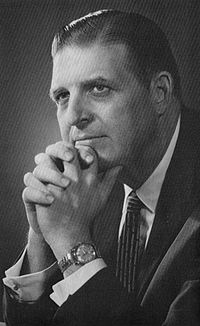

If Carl F.H. Henry hadn’t died in 2003, he would be turning 100 years old today. As I contend in Moral Minority, Henry inspired both conservatives and progressives toward social action. You wouldn’t know that based on Google Reader today. I’m only seeing establishment conservatives from the Gospel Coalition, like Justin Taylor, Russell Moore, and Al Mohler, honoring his memory.

If Carl F.H. Henry hadn’t died in 2003, he would be turning 100 years old today. As I contend in Moral Minority, Henry inspired both conservatives and progressives toward social action. You wouldn’t know that based on Google Reader today. I’m only seeing establishment conservatives from the Gospel Coalition, like Justin Taylor, Russell Moore, and Al Mohler, honoring his memory.

Here’s an excerpt from Moral Minority’s first chapter, in which I describe Henry’s ambivalent response to the Chicago Declaration:

Henry’s response to the angst, flamboyant rhetoric, and specific policy prescriptions of his younger colleagues was understandably ambivalent. After all, he was an elder evangelical statesman presiding over the muted social conservatism of Christianity Today, the National Association of Evangelicals, the Evangelical Theological Society, and other institutions he had helped to establish. Henry was no longer an evangelical provocateur. Yet he admired their heightened social consciences, and he knew that he was partly responsible for setting in motion a trajectory away from principled passivism. A postwar wave of economic prosperity, rising social status, a new rhetoric of engagement, and a transformed eschatology—all elements epitomized and driven by movement-builder Carl Henry—had brought evangelicals to the brink of sustained political activism.

Henry’s path out of a fundamentalist exile took many directions. It led to Jerry Falwell, to James Dobson, and to a conspicuous politicization on the right. It also led to John Alexander, Jim Wallis, Mark Hatfield, Sharon Gallagher, and a movement of progressive evangelicals. The story of postwar evangelicalism, a politically contested and fluid movement, does not equal the prehistory of the Christian Right. In the 1970s the future of a newly heightened evangelical politics remained strikingly uncertain. Whether it went left or right was secondary to Henry’s more fundamental call for evangelicals to go public with their spiritual commitments.