As a child, my Mennonite family taught me the way of peace. They did so in part by telling the story of Hannes Müller, who in 1749 traveled from his home on the border of France and Germany to the port of Rotterdam in Holland. There he boarded a ship called the Phoenix, which carried him to the port in Philadelphia. Then traveling overland, he journeyed to Berks County, Pennsylvania, near the city of Reading and set up a farm.

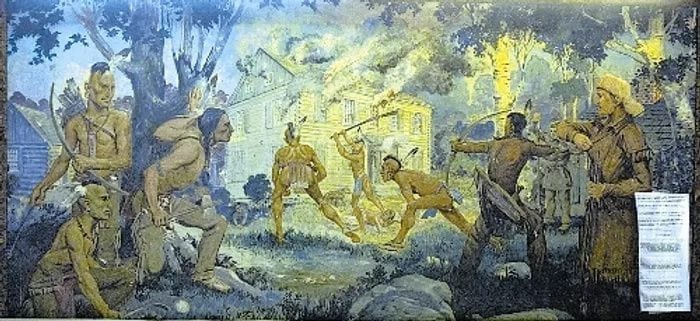

About eight years later, in 1757 during the French and Indian War, “Wounded John” Miller, as Hannes Müller came to be called, met with tragedy. As he was plowing in a field, he noticed an unusual cloud of smoke rising from the Jacob Hochstetler farm nearby. Since he had recently heard tales of Indian massacres in the area, he left his plow and fled into the forest. At the same time several members of the Delaware tribe burst into the clearing from the direction of the burning homestead. Terrified, he was able to lose his pursuers among the dense trees. An alternate version is that John was chopping wood, was captured, shot through the hand as a warning, and then released. Regardless, John Miller fared better than the Hochstetler family, one of whose descendants married one of John’s descendants, whose offspring eventually resulted in me more than two centuries later.

The Hochstetler family was massacred. The sons had guns and ammunition in the home and were ready to defend the family, but the father, firmly believing in the doctrine of non-resistance did not give his consent. In vain they begged him. He told them it was not right to take someone’s life, even to save one’s own. Consequently, a son and daughter were tomahawked and scalped, and the mother was stabbed through the heart with a butcher knife and scalped. As the knife came down on her, Mother Hostetler glanced her eyes heavenward and screamed in her mother tongue, “Oh, Herr Yesus!” The father and another of his sons—who their captors decided not to kill because they were intrigued by his blue eyes—were taken captive and led into the frontier. They were released years later as part of a prisoner exchange in the French and Indian War.

The lesson of the story: Peace is difficult, but it’s the way of faith in God and obedience to the teachings and example of Jesus. My evangelical Mennonite church taught me that killing fellow believers is a violation of Christian discipleship—and that killing heathens, which might send them to eternal torment, is a violation of evangelism. Because the Hochstetlers sought peace, they should be viewed as pacifist heroes. As one account puts it: They remained “faithful in the hour of sorest trial.” As a ten-year-old boy, I was transfixed by the story, and I interrogated my own soul. Would I be courageous enough to not use violence to defend myself?

This was a true story. But there was another story that my history teachers had not told me. My ancestors may not have brandished guns and forcibly taken land from indigenous peoples. But they were nonetheless complicit in what we might call the European invasion of North America.

Indeed, their farms would not have been possible without the backing of the British Empire. Their farms would not have been possible without wars and dozens of broken promises and treaties between the U.S. government and various indigenous people groups. Their farms would not have been possible without help from the land offices of Pennsylvania and Maryland that gave them land designated as “vacant.”

This second story, which is more attentive to the historical context of my ancestors, exposes their inaction in the face of terrible injustice. In this case, unlike the first story, inaction doesn’t seem quite so peaceful.

That I can tell two stories that are simultaneously so different and so true exemplifies what Chimamanda Adichie, a Nigerian-born writer, has called “The Danger of a Single Story.” When she arrived in the United States to attend college, she found that her classmates had stereotypes about her. There was the funny story of a new college roommate who wanted to hear some of her “tribal” music only to be disappointed when she pulled out a cassette of Mariah Carey. There were the less funny experiences of people assuming she had been a starving, naked child with flies hovering around her encrusted mouth. And in her TED talk, Adichie explained that stereotyping is not a singular vice of Americans, noting that she too gave in to a single story in assuming things about Mexicans and white people.

What my Mennonite church should have taught me was that the sacred texts of my tradition do offer a model of telling multiple stories. The story of Israel’s beginning is told through multiple memories. Later on King David is narrated as a violent general, a philanderer, a murderer, and a “man after God’s heart.” The New Testament opens with many gospel accounts, presenting four quite different accounts of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. The stories we hear depend much on the personalities, backgrounds, and vocations of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

All of these stories demonstrate the terrible and beautiful complexity of the human condition. We see it in David. We see it in my Hochstetler ancestors who were generous and peaceful even as they were structurally complicit in theft and violence. If we interrogate our own souls and contexts, we’ll see it in ourselves. Even when we don’t personally commit violence, we can live lives that aren’t peaceful. In short, nonviolence is not peacemaking.

It’s a sobering reality that should give us pause about overly valorizing our own heritage. There is danger in telling a single Mennonite—or Wesleyan or Catholic or Reformed or Buddhist—story.

David,

I’ve followed your “pilgrimage” postings with interest. Thanks for including me.

Your thoughts on the dangers of a “single story,” along with the examples from your personal history and from scripture, was especially insightful, I thought.

I did not grow up in a Mennonite or Amish home, but I did grow up with a Swedish Baptist father who had a strong personal commitment to peace that he had learned from those who had influenced him religiously. He taught the same to me and my two brothers, all of us then registering as conscientious objectors.

We have retained that commitment, but we, like you, remain very aware of the many ways that we live beneficently in a place that was shaped and fashioned by those who were practicing (and are still practicing) a devilish degree of violence and greed. So, as you suggest, our efforts at making peace is endlessly a task unfinished. The call to “repent, for the kingdom of God is close at hand” is a call that none of us can claim to have fully answered as yet.

Appreciatively,

Mark Olson

>

Just to live — anywhere — feels complicit with injustice on many levels! “You’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t syndrome.” How do we best avoid paralysis, aloofness and apathy? We want to remain open to seeing an event through many lenses, but eventually we have to settle/root primarily in one communal understanding, don’t we?

Very thought provoking. Have enjoyed your posts. Skip Elliott